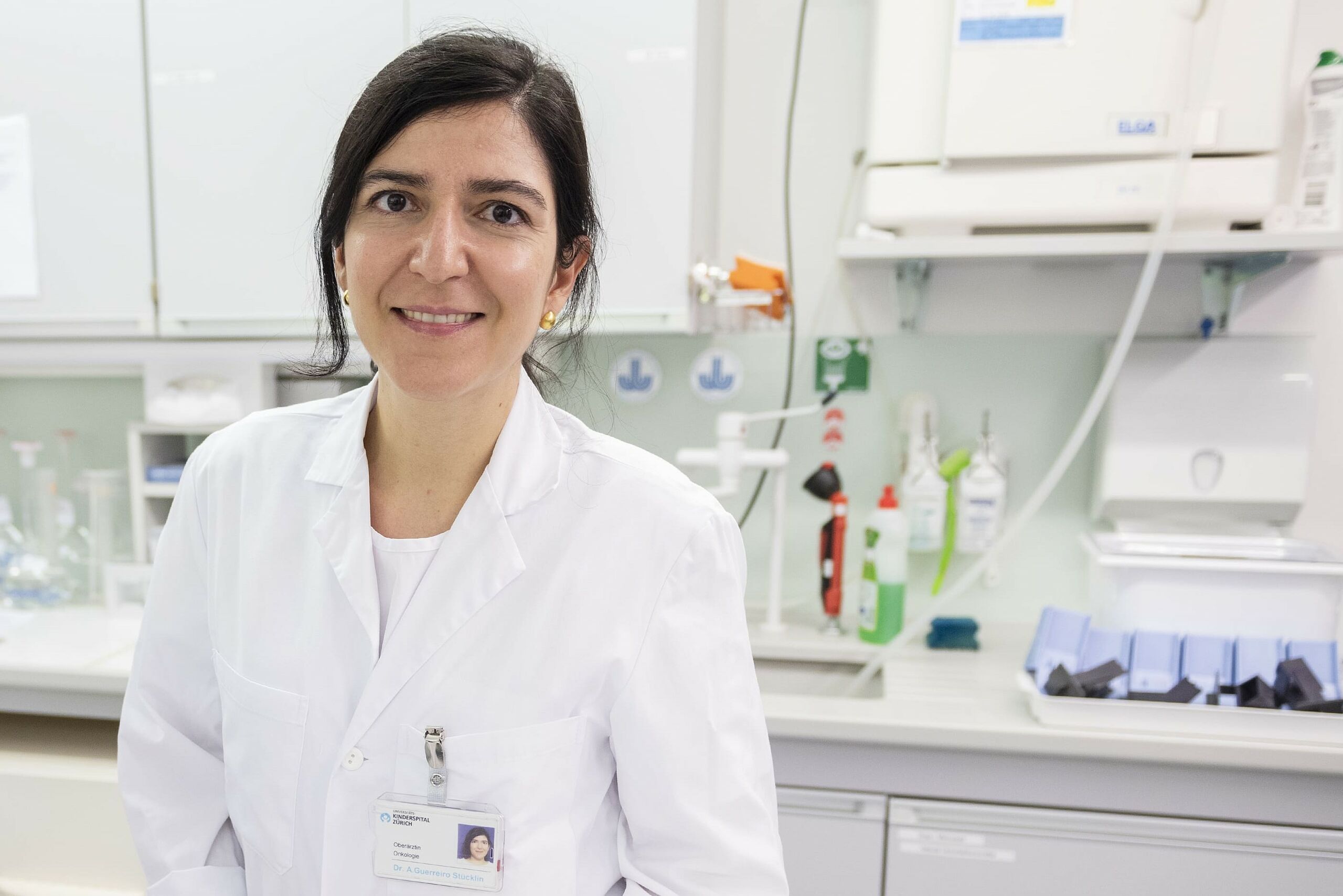

Interview with

Prof. Ana Guerreiro Stücklin, MD PhD

Neuro-oncologist and senior physician at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich, specialising in brain tumours in children and adolescents. She has received several awards for her outstanding research. Her findings help to improve cancer therapies and develop new treatments.

Ms Guerreiro Stücklin, you carry out research into brain tumours in children and adolescents. Why is that of particular interest to you?

It is important to know that brain tumours are the second most common type of cancer and unfortunately also the most common cause of cancer-related death in childhood. Even though the chances of survival have improved considerably in recent decades thanks to medical advances, many types of brain tumours in children still remain incurable. And I want to find out “why”. In the lab, my team and I investigate which molecules are responsible for the tumour tissue not responding to treatment. Our long-term goal is to develop better treatment options for affected children.

You have already received several awards for your research work. What did you focus on in that research?

In general, we are trying to better understand the biology of brain tumours in order to find new drugs for treating tumours that have a particularly poor prognosis. Even though some children can be cured, there are patients for whom the therapy simply does not work. In addition, there is a risk of relapse even after successful treatment. In the case of a recurrence, the tumour may have changed and become so aggressive that – in its new form – it is no longer curable. While there are many studies that focus on the types of tumour detected in the initial diagnosis, there aren’t many that focus on recurrence. Medulloblastoma, for example, the most common malignant brain tumour in children, no longer responds to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy when it recurs

What exactly is your project about?

Nowadays we know a lot about the genetic “blueprint” of tumours but that doesn’t help us deduce how the cells will react to cancer drugs. In the laboratory, we therefore examine tumour cells from the clinic and test them with newly developed drugs. We investigate which of these many drugs are most effective for a particular tumour group, for example because they inhibit growth. In some cases, the research results we gain from these tests can then be applied to the individual therapy. In addition, we work on the development of new treatment concepts. In this way, findings from our experiments are taken into account in new study protocols that can be used to treat patients in the future. Even though the basic research takes place in the laboratory, the questions come from everyday clinical practice and the answers are in turn incorporated into the therapies – our work thus directly benefits children with cancer.

What do you think are the biggest challenges?

Our goal is to develop new therapeutic approaches to improve prognoses for children with incurable brain tumours. Continuous research is enormously important in this, along with ongoing financial support. That is why we are so grateful for donations and grants because we can make much better use of our skills in the lab than in the search for additional funding.

What motivates you most in your work?

As a scientist, I am of course fascinated first and foremost by research in the field of oncology. But as a doctor, my main concern is the well-being of my patients. Research opens up a whole world of possibilities that gives us all hope that children with incurable cancers will in fact one day be able to be cured. Every patient is unique – like a puzzle that we have to solve. Thanks to recent research, we know that cancer tumours are far more diverse than previously thought. For this reason, every tumour should be examined individually so that every child can receive the best therapy. New research findings are the only way for us to ensure that seriously ill children receive better therapies and thus better prospects of being cured.